Background

The current political and pesticide use is flawed because it indirectly promotes farmers to use unsustainable practices that cause significant damage to nearby water resources. In this case, poor practice is defined as the inappropriate use of pesticide or the use of pesticides that inherently threaten water supplies. Three factors that promote poor practice are variance in expected pest levels, farmer subsidies provided by governments, and uncertainties in regulating pesticides. Given that farmers are never certain of the pest levels for any given year, farmers have the incentive to err on the positive side which exacerbates pesticide runoff. Any loss in profit due to excess application is offset by government subsidies. Uncertainty in research makes it difficult to fully integrate the dangers of individual pesticides into public policy and practice.

Pesticide run-off from farms threatens to pollute both groundwater and surface reservoirs in developing and developed countries. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that five percent of pesticides applied annually onto the field leech into the surrounding water rendering the water resource un-drinkable [1]. Even though this is a small fraction of the total amount of pesticide applied, recovering contaminated water systems is expensive. Estimates show that the U.S alone would need to spend $2.2 billion annually to reverse environmental damages caused by pesticide runoff [2].

The cause behind poor pesticide practices differs between developed nations and developing nations. In developed nations, poor practice arises from uncertainty in regulating of new pesticides and from fear that under-applying will lead to lower yields. Likewise, in developing nations, poor practice arises from market competition with illegal or unlicensed pesticide and from the lack of education or concern for over application.

Solutions

Overcoming Uncertainties in Regulating Pesticides in Developed Countries

A recurring problem in developed nations is dealing with poor public policy and practice that result from incomplete risk assessment of new pesticides. Regulating agencies, such as EPA, currently tackle this problem by requiring pesticide companies to conduct extensive testing prior to licensing. However once the pesticide is approved, few efficacy or safety trials continue after the first few years of full production. Thus, the guidelines produced by regulating agencies inevitably fail to account for long-term and scale effects. In addition, the only companies capable of licensing a product are those that can afford the initial investment.

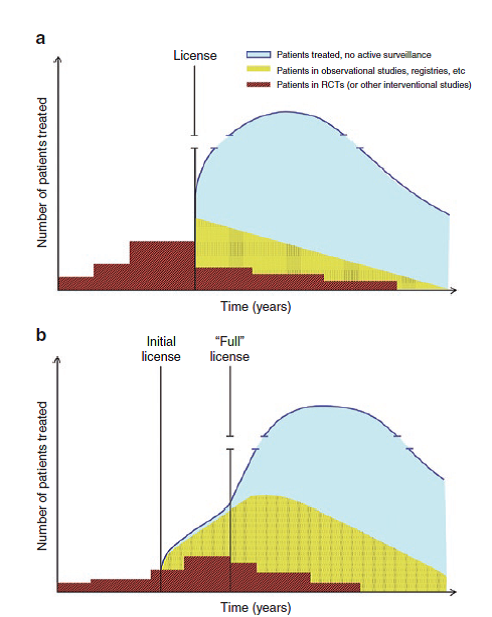

Figure 1: The top figure represents the current licensing process for pesticides where value of sales is on the y axis and time in years is on the x-axis. The burgundy blocks represents the number of trials being conducted on the pesticide. The represents the farms participating in observational studies. The below figure shows how sales and studies would be affected using an adaptive scheme to licensing [3].

Uncertainty and high initial investment into research are similar problems dealt with during the development of pharmaceuticals. Professionals working in pharmaceuticals are beginning to take an alternative approach to patenting called adaptive licensing to address these issues. The licensing period in adaptive licensing is divided into two phases instead of one. Phase one of licensing requires a less stringent proof than a full license but has restrictions on the quantity of sales. By allowing a period of randomized trials, public policy would be made with less uncertainty than policy made under a one license scheme [3]. The lower cost of the initial license also opens the pesticide market to smaller firms which fosters innovation [4]. Since both industries are evolving in very similar ways, an alternative to the current approach in pesticide regulation may be to split the licensing period into two like the pharmaceutical industry.

The approach would be modified to better fit pesticide management. Regulating agencies (e.g. EPA) would only approve initial licenses for prospective pesticides that adhere to environmental guidelines and possess the possibility of improving safety or efficacy of current practices. This license would limit the total quantity sold and place special guidelines when appropriate. If the pesticide is determined unsafe any time during this initial period, it will be immediately recalled. The time difference between the initial license and the full license would be larger than that in the pharmaceutical industry because effects in the environment accumulate more slowly than that in the human body and difficult to observe. This period would depend on the risk assessed during pre-licensing trials and on the time it takes to eliminate that uncertainty.

During the full licensing of the pesticide, policies can be enacted that utilizes more complete information about environmental to make the product more or less expensive through mandatory liability insurance that must be purchased by companies marketing the pesticide. Companies would be forced to purchase liability insurance for the initial license as well as the full license. Pricing of insurance would depend on data generated during the trial periods. In order to ensure that affiliation does not bias trial results, research groups during the initial trial must be funded by neutral regulating agencies and not through companies. To offset this cost, there will be a licensing fee to transition into the initial license. The pricing for the licensing during the initial period, however, is fixed so that companies will be allowed freedom of research. Revenues gained from mandatory insurance will be used to fund the review boards and clean-up projects that may be needed to remediation.

This approach creates an initial population of users that would experimentally determine optimal practices or reveal errors in product design. By allowing this test group to learn and experiment with proper techniques, guidelines and recommended can be refined and packaging would include optimal practices and help remediate errors. The full population of users will struggle less due to enhanced learning with the help of more experienced users. This therefore would on average improve pesticide practices.

Adaptive licensing improves the conditions of all those involved – the environment, the regulators, and companies. These benefits are enumerated in the list below.

- More companies can enter the market with a potential product

- Net cost for production of pesticide from the research phase to market phase decreases

- Environmental remediation projects are funded

- Cost of product for consumer decreases or stays the same

- Average safety of products fully licensed would increase.

- Fewer cases of unsuspected groundwater contamination due to use of safer products

- Lower chance of litigation for companies that accidently

However, two shortcomings of this approach are increased risk of environmental damage during the initial licensing period and difficulty in adoption. Increased risk is addressed by requiring insurance payments from pesticide companies and difficulty in adoption is addressed below.

Initiating the Change to Adaptive Licensing

Implementing adaptive licensing would require regulating agencies (e.g. EPA) to change its administrative framework and create a secondary committee that works outside of that regulating agency. This type of change would require governmental approval and support from both companies and from the regulating agency. Although adaptive licensing is not a general paradigm in the field of regulating pesticide, it would likely be implemented once the idea becomes prominent.

One way to achieve support is to rely on word of mouth within the regulating agency and the pesticide industry. Legislation then must be drafted and finally legalized. The steps below should be implemented by a group dedicated to the redesign of the pesticide licensing process.

Step 1: The first steps would be to invoke governmental concern for pesticide contamination and then offer this as a possible solution to legislators. Political agenda begins within the public and therefore the first step is to change mindsets about the water and the environment through non-governmental organizations.

Step 2: Step two would be to find prominent members of the political/scientific community to support adaptive licensing and publish a joint paper detailing the benefits and shortcomings of this new approach. The joint publication should include authors from industry, academia, and government to increase the impact of the paper. It is pivotal to gain support from all sides of those affected in order to ensure a smooth transition from a one step licensing to a two step licensing process.

Step 3: Once the idea enters the legislative process, individuals should contact non-governmental organizations similar to Pesticide Awareness Network and work together to create systems to ease the adjustment into a two phase licensing process.

References

1. Kellog, R., Nehring, R., & Grube, A. (2000, February).Environmental indicators of pesticide leaching and runoff from farm fields. Retrieved from http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/technical/?cid=nrcs143_014053

2. Pimentel, D., 2005. Environmental and economic costs of the application of pesticides primarily in the United States. Environment, Development and Sustainability 7 (2), 229–252.

3. Eichler, H., Oye, K., & et al. (2012, March). Adaptive licensing: Taking the next step in the evolution of drug approval. Retrieved from http://cbi.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/clpt2011345a.pdf

4. Hogg, S. (2011, November). Why small companies have the innovation advantage. Retrieved from http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/220558

5. Environmental Working Group (2004, November) Farm subsidy primer. Retrieved from http://farm.ewg.org/subsidyprimer.php