Background

In order for humans to preserve and protect our global freshwater supply, we support conservation. World powers and corporations are much more likely to make changes that protect global water security if the citizens rally behind such changes. By creating global awareness of the use of water in everyday products, one could shift the demands of consumers towards more water-friendly products, hence persuading companies to produce such merchandise.

The virtual water “contained” in a product, or its water footprint, is the amount of water that was directly or indirectly used or contaminated in its production. For example, the global average virtual water consumption for one ton of chicken meat between 1996 and 2005 was 4,300 cubic meters, which include the water that was needed to produce the feed of the chickens, the water they drank, and the water needed for servicing the farm and the slaughtering process [6]. Other than sounding like a lot of water, this number has no special meaning to the average person. However, when compared to quantities such as 15,400 cubic meters, or the water footprint of one ton of beef cattle [7], or 50 cubic meters, the amount of water the average household uses in a month [8] one realizes that the first number is significantly smaller than the second one, and that that difference is equivalent to the water that thousands of households around the world are lacking.

When a person buys any foodstuff, he or she is inherently buying its virtual water as well. If we add up the numbers, people end up buying thousands upon thousands of liters of virtual water per day that they don’t appreciate, unless they have investigated the water footprint of each of the products they buy. If labels were to be placed on every product, informing the consumer of the virtual water that went into its production, consumers would be made aware of the amount of water they unconsciously use, potentially changing their purchasing habits.

Solutions

The agricultural industry is the most crucial market to target because it is responsible for 70 percent of the global freshwater use [9]. There are far more options for farmers to employ in order to reduce their water footprints, such as different irrigation methods, genetically modified organisms, monitoring fertilizer and pesticide use, as compared to other types of companies’ options, such as chemical treatment. Also, it is less likely that manufacturing companies will agree to label their products’ water footprint because of the complexity of making such a calculation, considering all the raw materials’ or supply chain’s water footprints that would go into the net water footprint. Therefore, while it is encouraged for every company to participate in virtual water labeling, the most important market to focus on regarding this solution is the agricultural industry.

Governments all around the world, especially where there’s a strong consumer culture, should legislate that all farms, regardless of scale, should be required to calculate and label the virtual water of their product. Every product originating from a farm has a monetary value. Such value shall be accompanied by the volume of virtual water under this new labeling system. Since this virtual water volume does not fluctuate with the markets or the currency of the country, it won’t change as the product gets sold.

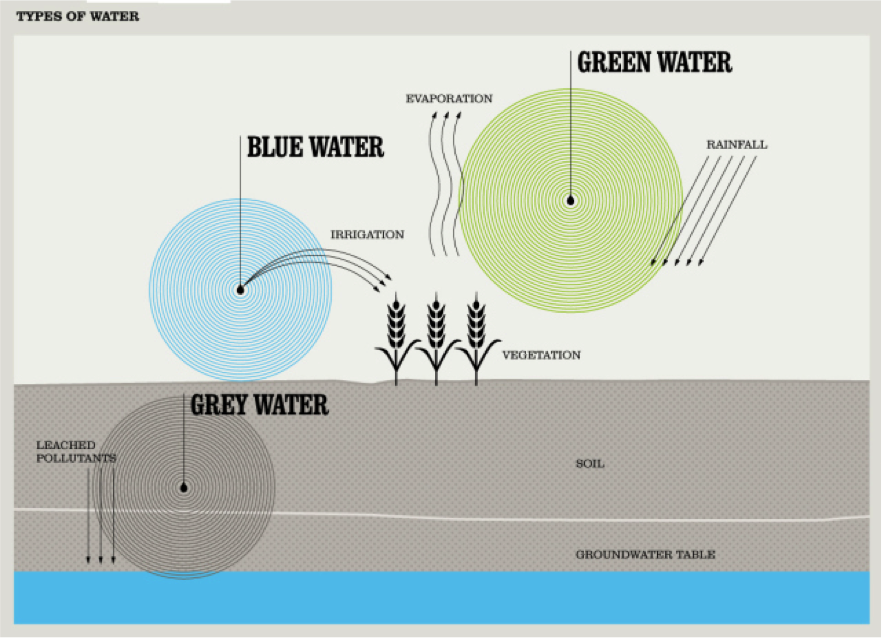

Consider a farmer who grows coffee in Brazil passively using large amounts of rainwater that falls on his fields. By contrast, a soap manufacturer does not use rainwater and barely withdraws water from nearby lakes and rivers, yet pollutes a large portion of one of the rivers nearby. However if the soap manufacturer’s portion of water is significantly less than the quantities of rainwater that the farmer in Brazil uses, the company’s water footprint would be lower. Yet, the soap manufacturer is affecting the global water supply and ecosystems more than the farmer, since rainwater is falling regardless of the presence of a farm, but that’s not necessarily the case with pollution, since contaminants spread, reach larger water bodies and can potentially harm vulnerable fauna.

Figure 1: Green, blue and grey water presented as part of the water cycle [9].

Aware of this ambiguity, agencies like the Water Footprint Network that calculate virtual water uses divide the water footprint of a product into three categories: blue, green and grey water, as illustrated on Figure 1. Blue water refers to water in freshwater lakes, rivers and aquifers; green water refers to water from precipitation that does not become runoff, either by staying stored in the soil or evaporating; grey water refers to the total volume of freshwater polluted [6]. Taking this into consideration, the format of the virtual water label should distinguish between these types. Given that green water does not become runoff, taking advantage of it is much preferred to producing grey water. Thus, by differentiating between these types on the labels and informing through the media about their meaning, consumers will be adequately equipped to make the best decision among which products are truthfully the best for the environment and water supply.

Although it is highly recommended that farmers and companies follow the Water Footprint Network’s Water Footprint Assessment Manual [1] to calculate their produce’s virtual water, other methods may be used if approved by specialists and the respective governing body, such as the national bureaucracy. Inspections are to be held in a periodic manner, preferably with time periods of six months or less. If agencies that protect the public health by monitoring the nation’s food supply or that protect the environment do not exist, like the FDA and EPA in the United States, a new bureaucratic committee is to be formed by the nation’s governing body to specifically regulate the virtual water labeling requirement.

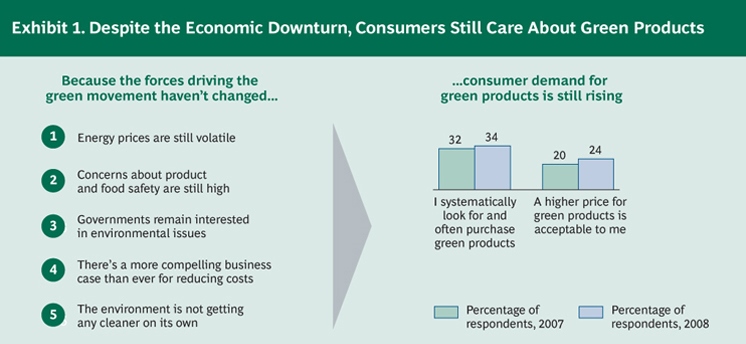

By connecting products with their water footprint, consumers will be given another important consideration when choosing a product. Recent studies like Boston Consulting Group/Lightspeed Research survey in 2008 show how consumers around the world (including countries like Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States and China) prefer “green” products, even to the point of being willing to pay a higher price for it, regardless of a tight budget. That is, if they truly believe that these products are either healthier or better for the environment [5]. Figure 3 illustrates the reasoning behind this trend. When given the choice between products of higher water footprints versus lower ones, especially with the same price but not excluding products with slightly higher prices, consumers are more likely to pick the latter.

Figure 2: Consumer trends regarding green products [5]

From a consumer perspective, this legislation could potentially shift current shopping habits that are not influenced by water footprints towards ones that do. The world currently faces an overall increase in per capita income, which increases meat consumption per capita [2]. Through acknowledging the large water footprint of meat, as compared to grains and other vegetables, people with an increased income will be more reluctant to be part of the before mentioned trend and could potentially utilize that extra income to buy eco-friendlier products, including those with a lower water footprint. In comparison, if consumers show a preference for products that used less water to be produced, farmers and companies will not only make efforts to decrease their water usage, but could find it worthwhile to invest in new technologies that will provide them with this new competitive advantage.

Feasibility

The biggest problem with virtual water labeling is that, while the idea and procedure seem straightforward and clear, it may pose a challenge for bureaucracies to monitor the methods farmers employ and how accurate the results truly are. Also, there is no guarantee that there will be a significant shift of consumer demand because of these labels, since companies might add into the price of the product the costs associated with acquiring new technologies to decrease their water consumption, such as new irrigation equipment, to a point that the cost of such product will turn away even the most eco-friendly consumers.

However, these concerns are addressable. To aid monitoring, governments would just have to standardize and coherently specify the virtual water calculation methods required, and ask for a clear continuing report. In terms of price raising, governments could subsidize farmers in acquiring technologies. This way, the costs would be alleviated, and the prices would not be affected by the regulation.

Case Study

Figure 3: Concha y Toro Winery, 2010 [4]

As of today, virtual water labeling has yet to be implemented as a national policy. Still, a certain number of companies have taken the initiative of labeling the water footprint of their products. One such example is Concha y Toro. Concha y Toro is a world renowned Chilean winery that, in partnership with the Water Footprint Network, became the first and only winery in the world to measure their wine’s water footprint in 2010 [3]. Coincidentally enough, it is Latin America’s largest wine exporter and has been recognized and publicized all over the globe for its emphasis on environmentally-friendly wines [11]. The years they won the award coincided exactly with the years following to their water footprint labeling [4]. This shows that, while it could represent an added cost to companies, in the long run they could turn this requirement into an advantage by reducing their water footprint.

Conclusion

Explicitly fundamental to global water security, defined by Mission 2017 as the people’s ability to maintain a constant and sufficient supply of clean water, the people must be made aware of their role on global water usage. This can be achieved through governing powers requiring virtual water labeling, especially in the agriculture industry, and periodically monitoring that labels are kept accurate. Once awareness is created, people will shift their purchasing preferences towards more water-friendly goods, and producers will comply accordingly. Hence, virtual water labeling is a solution for the depletion of water, particularly from the agricultural sector.

References

1. Arjen Y. Hoekstra, A. K. (2011). The water footprint assessment manual: Setting the global standard. London: Earthscan.

2. Brown, F. (2009, September 2). Meat consumption per capita. Retrieved January 24, 2013, from The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/datablog/2009/sep/02/meat-consumption-per-capita-climate-change

3. Concha y Toro Winery. (2010). Responsible Water Management. Retrieved November 24, 2013, from Concha y Toro: http://www.conchaytoro.com/desarrollo_sustentable/en/manejo_agua.html

4. Concha y Toro Winery. (2012). The Company History. Retrieved November 26, 2013, from Concha y Toro: http://www.conchaytoro.com/web/the-company/history/

5. Joe Manget, C. R. (2009, January 20). Capturing the Green Advantage for Consumer Companies. Retrieved 11 24, 2013, from BCG Perspectives: https://www.bcgperspectives.com/content/articles/consumer_products_sustainability_capturing_green_advantage_for_consumer_companies/

6. M.M. Mekonnen, A. H. (2010). The Green, Blue and Grey Water Footprint of Farm Animals and Animal Products. Delft: UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education.

7. Mesfin M. Mekonnen, A. Y. (2012). A Global Assessment of the Water. Enschede: Ecosystems.

8. Morelli, A. (2013). What is Virtual Water? Retrieved November 27, 2013, from Angelamorelli.com: http://www.angelamorelli.com/water/

9. Nations, U. (2009). Statistics: Graphs and Statistics. Retrieved 11 24, 2013, from UN Water: http://www.unwater.org/statistics_use.html

10. SAB Miller Plc. (n.d.). Water Footprinting: Identifying & Addressing Water Risks in the Value Chain. Retrieved November 26, 2013, from SAB Miller: http://www.sabmiller.com/files/reports/water_footprinting_report.pdf

11. Wines of Chile. (2013). Wineries. Retrieved November 24, 2013, from Wines of Chile: http://www.winesofchile.org/wineries/members-access/concha-y-toro/