The problems of the status quo

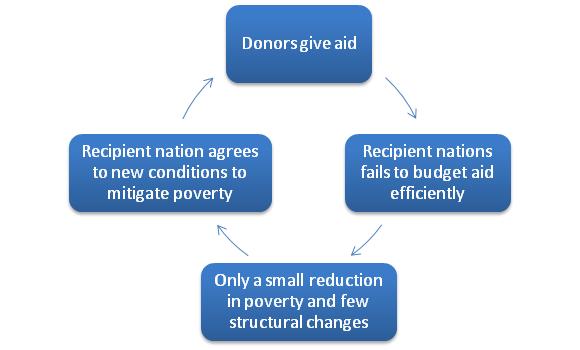

Conditional aid and lending are defined as capital, food or other incentives given or loaned “in exchange for policy reform and structural adjustment” (Ramcharan, 2002). Such aid forms a substantial 7% to 8% of GNP in the average developing nation (Svensson, 2002). In theory, conditional aid is the most efficient and effective means of meeting the needs of a developing nation while affecting political change for the better. However, the majority of aid fails to achieve reform, due, in part, to the cycle of corruption and mismanagement that arises in most conditional aid cases (Kanbur, 2008). The cycle, adapted from Kanbur’s report on conditional aid failures in Africa, is illustrated on the right.

Conditional aid and lending are defined as capital, food or other incentives given or loaned “in exchange for policy reform and structural adjustment” (Ramcharan, 2002). Such aid forms a substantial 7% to 8% of GNP in the average developing nation (Svensson, 2002). In theory, conditional aid is the most efficient and effective means of meeting the needs of a developing nation while affecting political change for the better. However, the majority of aid fails to achieve reform, due, in part, to the cycle of corruption and mismanagement that arises in most conditional aid cases (Kanbur, 2008). The cycle, adapted from Kanbur’s report on conditional aid failures in Africa, is illustrated on the right.

Although the recipient nation failed to achieve meaningful political reform, the small reduction in poverty is enough to encourage future donations. This cycle also perpetuates corruption, as corrupt governments are aware that they may renege on conditions of aid without losing the financial aid itself (Kanbur, 2008). As a result, the current aid system may be contributing to the long-term problem of corruption without alleviating hunger and poverty.

Solution 1: Competitive aid

Ideally a solution will reduce the inefficiencies of conditional aid without reducing the net effectiveness and amount of aid donated. One of the central problems of the current aid system is the one-to-one relationship between donor and recipient (Kanbur, 2008). Matching one recipient to one donor provides for a targeted approach, which is desirable, but also risks too narrow a scope. If the conditions of aid are not met, then the cycle above could take place and the aid would go to a corrupt or inefficient government, making large-scale structural reform unappealing.

However, a system where the donor considers several potential recipient nations for aid donations is far more likely to achieve conditions placed on the aid and lead to tangible improvement and alleviation poverty. It would work as follows (Svensson, 2002):

1. The donation party allocates a certain amount of money and selects several hopeful nation sharing similar characteristics (eg. West African nations)

2. Conditions are set (eg. increased transparency) and progress is measured over a period of time

3. Funds are apportioned to each candidate nation, proportional to progress in conditions set earlier

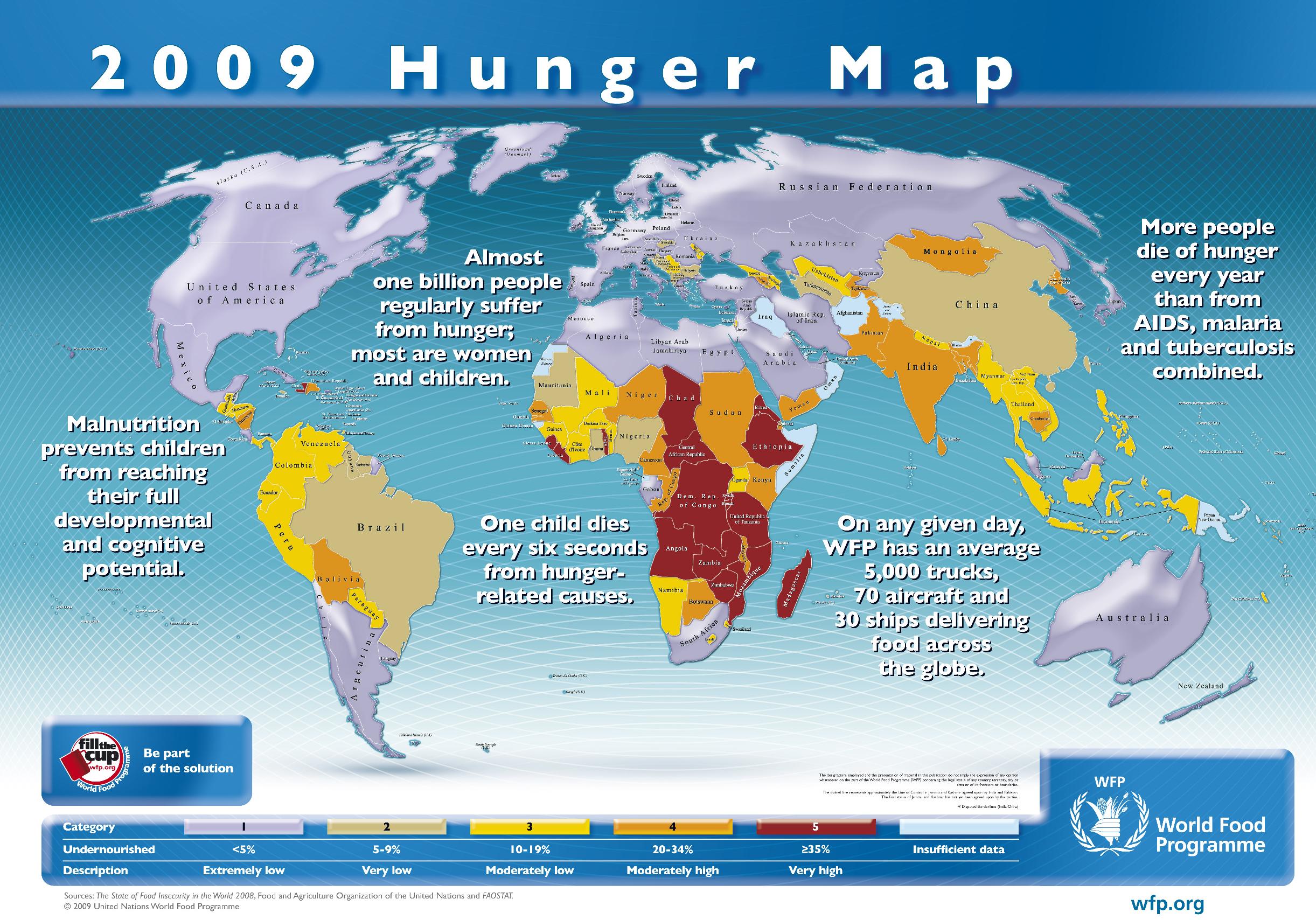

Competition creates the incentive that is lacking in the current system of conditional aid. By making aid conditional to relative progress, nations must show tangible improvement in order to receive aid. Furthermore, the aid is directed towards countries that would benefit the most as inefficiency in governments would solve themselves in order for the nation as a whole to receive more aid. This aid can then be distributed through a more transparent system to the impoverished and hungry. According to the World Bank, if this donor aid is “redirected towards poor countries with good policies, more than 80 million people could be lifted out of poverty for the same aggregate level of foreign aid” (Svensson, Collier & Dollar). The link between poverty and hunger is unmistakable; if aid is allocated efficiently, the number of hungry people will demonstrate a comparable decrease.

Implementation

The aid competition solution proposed is not comprehensive. For aid-receiving nations that are stable and transparent, a system like this is unnecessary. Furthermore, for small projects that essentially circumvent national governments and bring aid directly to the people, the current one-to-one system has largely worked. In Sauri, Kenya, “agricultural yields have doubled [and] child mortality has dropped by 30 percent” due to a pilot program following the current system of conditional aid (Gettleman, 2010). On a larger scale however, governments have a role to play. National governments, no matter how corrupt and opaque, are the only entities that have jurisdiction over an entire country. Thus, competition for aid can be used as a tool to reduce corruption in governments, which in turn, can reduce poverty (as shown below, poverty and corruption are strongly correlated).

(Corruption Perceptions Index, 2009 Hunger Map)

In order to implement such a major change in the method of distributing aid, a change in mentality needs to take place among donors as well. The United Nations provides an international platform to do so. By drafting a resolution calling for all aid based on a donor-recipient nation framework to be competitively allocated, and having it ratified by the UN, donors would be made more aware of the problems facing the aid situation today. The competitive aid based approach could be touted as an alternative to the corruption-riddled present system. If donors are unwilling to adopt such a comprehensive change, it is reasonable to propose a trial of the plan. For a period of five years, several donor nations will adopt competitive aid as their strategy in offering foreign aid. The results of such a policy can be studied and presented to determine further action. In the worst-case scenario, the recipient nations in one aid competition may collude in minimizing improvement while still receiving aid in the end. This is highly unlikely however, due to the tendency of nations to compete and their desire to maximize incoming aid.

Solution 2: Transparency committees as a means to enforce conditions

Ramcharan, R. (2002, November). How does Conditional Aid (not) Work?. In International Monetary Fund. Retrieved November 23, 2010, from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2002/wp02183.pdf

Svensson, J. (2002). Why conditional aid does not work and what can be done about it? [Electronic version] Journal of Development Economics, 381-402.

Kanbur, R. (2008, October). Aid, Conditionality, and Debt in Africa. Africa Notes. Retrieved November 23, 2010, from http://www.einaudi.cornell.edu/files/content/848/Aid_Conditionality_and_Debt_in_...

Collier, P., Dollar, D., (1998). Aid allocation and poverty reduction. Policy Research Working paper no. 2041, World Bank.

Gettleman, J. (2010, March 8). Shower of Aid Brings Flood of Progress. In New York Times. Retrieved November 23, 2010, from https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/09/world/africa/09kenya.html

2009 Hunger Map (2009). In World Food Program. Retrieved November 23, 2010, from http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/liaison_offices/wfp185...

Corruption Perceptions Index 2010 Results (2010). In Transparency International. Retrieved November 23, 2010, from http://www.transparency.org/policy_research/surveys_indices/cpi/2010/results